In 1985, Oleg Vidov saw his chance and ran with it – literally. He’d been given permission by the USSR government to move to Yugoslavia to marry second wife Verica Stamenkovic several years earlier, but as his marriage disintegrated he was called to go back to Moscow. And so he made a daring plan to flee across the border to Austria for a chance of freedom from the Soviet regime.

“In the Soviet Union, an actor is not only an artist but a soldier on the ideological front whose purpose is to help the government disseminate ideas to the masses,” he would testify in front of the United States Congress three months after his defection, having been granted a refugee visa. “I was unable to compromise or conform.”

Where did Oleg Vidov grow up?

Born on June 11, 1943, just outside of Moscow, Oleg had the odds stacked against him from the start. His mother, Varvara, was a teacher, his father, Boris, a married man and a soldier that Varvara presumed was killed during World War II. As a child, the single mother took Oleg on her work travels, the pair journeying first in Mongolia, then later in Soviet-occupied East Germany.

“My dear mother gave me the most amazing childhood,” he revealed in hit documentary Oleg: The Oleg Vidov Story. “I got to experience something few kids from the Soviet Union could dream of – travelling outside of the country.”

But when Varvara was called to a posting in China, Oleg was sent to live with his aunt, Anuta, in Kazakhstan, near the Chinese border. It was here that he was first introduced to cinema and American films – something that captivated him instantly, opening up a whole new foreign world.

“I saw movies like Stagecoach (1939) and The Grapes of Wrath (1940),” he recounted. “I was crazy about Tarzan and Johnny Weissmuller. It was then that I started to think, I would like to become a film actor.”

In 1954 when Oleg was 11, he travelled with Anuta back to Moscow to be reunited with his mother. Anuta would also discover that his father Boris was, in fact, very much alive and now working as a government minister. He and Oleg met, and Boris began helping the family – who were living in a communal apartment with five other families – with money.

Still, it wasn’t enough to cover their expenses. And when his mother lost her employment after a politically motivated attack at 14, Oleg enrolled in night school so that he could work in construction during the day to support his family.

“If you really want to help us,” Anuta told her adoring nephew, “you must set big goals.”

And it was this idea which saw him turn up to Mosfilm studios at 17 years old, with no experience but big dreams. Yet Oleg was turned away at the door. He’d need connections, he was told.

Mosfilm was the leading production unit in the USSR, its movies the biggest and best of the Soviet era – as well as one that produced much of its propaganda. Lenin, who was in power at that time, understood that film was an important way to send the party message. There were strict censorship laws in place; entertainment could only portray communist life in a positive light.

Oleg knew this and chafed against it. But to act, he needed to play his part. And so, after landing a job at Moscow’s TV tower, he was finally accepted into the state film school, VGIK, in what he called “one of the happiest moments of my life”.

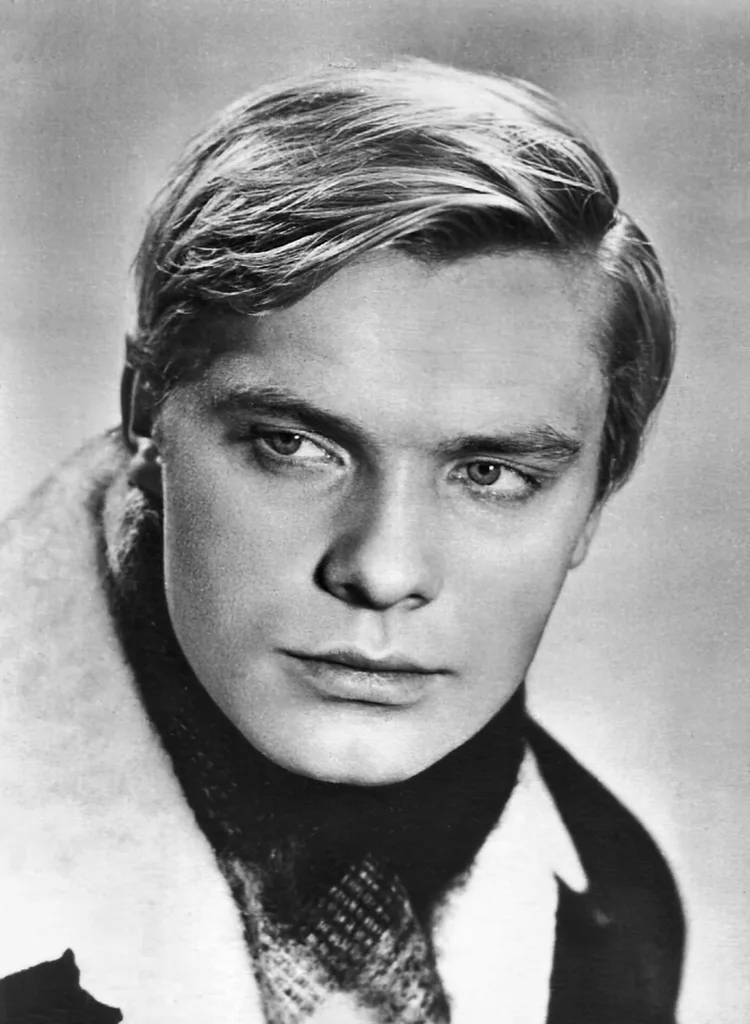

It wasn’t just acting Oleg was studying here, however. There were just as many classes geared towards teaching the official version of Soviet history. He began to get small parts, including his first with director Aleksandr Mitta in My Friend, Kolka (1961), in which Oleg is credited as “motorcyclist”.

“He was in his own world, the world of films,” Aleksandr reflects in the documentary. “The world of his friends and the rest just didn’t exist for him. Oleg was always 100 per cent above politics.”

What was the start of Oleg Vidov’s career like?

From the money he made from those early wages, Oleg made good on his promise to look after his family, giving his aunt funds to purchase cardboard insulation for the shed she was living in.

He certainly had promise and his startling good looks were starting to draw attention – and not just in Moscow. Danish director Gabriel Axel was so taken with the young actor’s talent that he applied for a visa to travel to Moscow, hoping to get permission to use Oleg as the lead in his 1967 film Hagbard and Signe.

There was a problem, though. The film, which was set in 1100, was to be shot entirely in Iceland. Only proven communists were allowed to travel abroad, and Oleg had certainly not signed on to the party. And so, he was called before a panel of men from the KGB who dangled the role like a carrot before him. If he signed a paper declaring he would behave like a good Soviet and not sleep with any Western women, he would be allowed to go.

Oleg signed the paper and set forth to Copenhagen to start pre-production. It was a total eye-opener for a man used to life in a Communist land.

“It felt like the city was illuminated with precious stones,” he would marvel. “There was so much electricity; so many lit up windows. People were friendly, they were smiling, a totally different world compared to the Soviet Union … Feeling the freedom was overwhelming.”

When the film was released, it was selected for competition at Cannes – astonishingly, Oleg was able to attend. He entered the festival an unknown and came out a star, with film offers from directors all over the world. Most of those requests, however, were shut down by the powers that were in Moscow.

It didn’t stop his career ascending at home, however. Nor did it stop him from finding love.

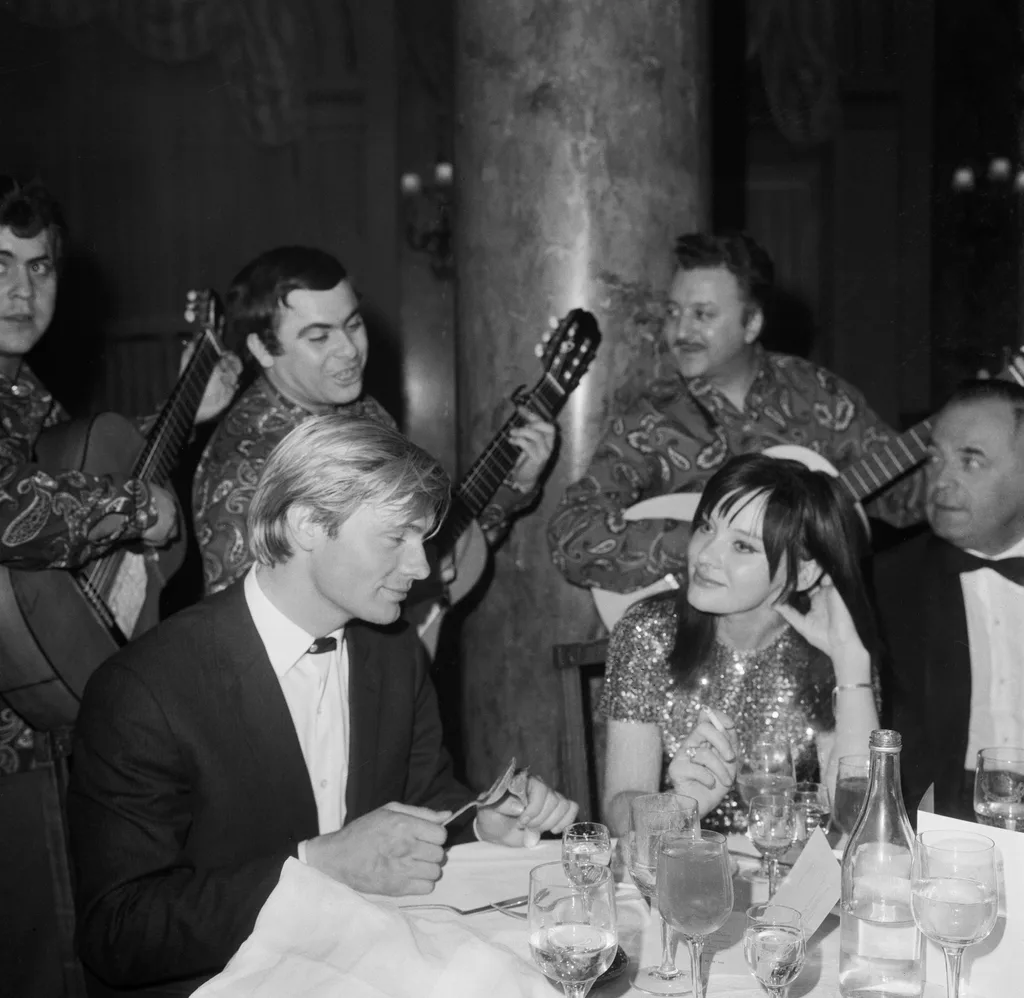

At a party, he would meet his wife-to-be Natalia Fedotova. Her father, Vasily Fedotov, was a KGB general and a close friend of Leonid Brezhnev – the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It was two very different worlds colliding.

In 1970 they wed and Oleg moved in with his parents-in-law, who resided in a glamourous building far from the humble shack he’d grown up in. The pair would attend lavish parties with the elite – something that jarred with Oleg, whose salary as an actor was a meagre one; far from what his Hollywood compatriots would expect.

He was the most popular actor of his generation, his good looks driving fans wild. So to help bridge the financial gap, he took paid tours around the country where girls would queue to buy postcards bearing his visage and signature. He and Natalya had a son, Slava, in 1971, but behind closed doors their marriage was falling apart.

He had starred in the first Russian Western, The Headless Horsesman (1973), and another Aleksandr Mitta project, Moscow, My Love (1974) – described as the Russian Love Story. But Natalia wanted Oleg to throw it all in to become a government minister. And when he made a film that criticised the Soviet transport system, that was Natalia’s final straw.

“I felt like a prisoner in that marriage,” he would say during their divorce. “After five years, our lives became intolerable. We agreed to live separately.”

Natalia took Slava, along with all of their communal property. When Oleg attempted to sue his ex-wife as a result, Moscow’s highest civil court ruled against him. As the film offers dried up he began receiving death threats. Oleg lost weight from the stress, his nerves seeing him on high alert and constantly looking over his shoulder.

When Oleg told a friend he needed to escape Russia, she suggested he should marry her Yugoslavian friend, Verica Stamenkovic, in order to do so. For Verica, it was love at first sight. For Oleg it may have been more desperation than love. The pair wed in 1982 but three years later, it was over. And so came the great escape.

When did Oleg Vidov go to America?

After fleeing the USSR, Oleg met American actor Richard Harrison, who helped him get to the US embassy in Italy where he was granted political asylum. Oleg made headlines: He was the first major Soviet actor to defect to the United States.

He also found new love. In Rome as he awaited his visa, he met American journalist Joan Borsten – she became wife number three in 1989.

And while America was the promised land he’d dreamed of, getting work wouldn’t prove easy. He loved his motherland while disagreeing with its politics. And in Hollywood, the only roles he was offered at the height of the Cold War were as Soviet villains. He would turn them all down.

But in 1987 came a lifeline. Director Walter Hill was casting buddy cop action film Red Heat with leading man Arnold Schwarzenegger. Jim Belushi would get the secondary role but they had another, far smaller role of a Russian policeman to fill.

“I didn’t know if he would take a smaller part because I knew he was used to playing in the big leagues,” Walter says in the documentary. “But he was also trying to become an established actor in the West and I believe it’s fair to say he was having a hard time … One sensed a great feeling of melancholy in Oleg about how difficult the transition had been. Although he didn’t regret it.”

Arnold was fascinated with Oleg’s journey and leaned on him for help with the Russian accent he himself had to learn for the film. It was the boost the Russian actor had needed. More, albeit small, roles would follow. And then the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991.

While Oleg would return to Russia for a visit, America would remain his home. It was here that he built a life with Joan and where he was finally reunited with Slava, who came to visit him. Astonishingly, he would also find another son, Sergei, who was conceived from a brief fling he’d had in 1977.

And with Joan firmly by his side, he acquired the rights to award-winning animation library Soyuzmultfilm Studio – helping to popularise the beautiful Soviet animation he’d grown up with around the world. The pair remained together until his death in 2017, following complications from cancer.

“Happiness belongs to the risk-takers,” Oleg would say later in his life. “No matter what they tried to take from me, they could not suppress my need to inspire others. I always follow my heart and that is my freedom.”

Oleg: The Oleg Vidov Story is available to watch on SBS on Demand.