Ahead of the release of her latest work, Pulitzer Prize-winning Australian-born author Geraldine Brooks sat down with The Weekly to discuss love, loss, and her latest novel, Memorial Days — released in January 2025.

It is hard to understand, in the face of sudden and tremendous loss, how the rest of the world can continue on as if nothing has happened. The shock after shock of a beloved person abruptly leaving and other lives going on as if normal when nothing is normal. When everything is ripped apart and irrevocably changed.

“All the clocks do not stop. No one silences the phone. The dogs continue to bark, the pianos to play,” writes Geraldine Brooks (referencing the poet WH Auden) in her memoir Memorial Days. “As much as I yearned to throw a black veil over my head and sit weeping under a yew tree, that was not possible.” There was so much that had to be dealt with in the business of death.

Instead, in the “gray mist” of grief, she put on an “endless, exhausting” performance. Before she left the house, she would prepare a face for the people she would see. “I felt,” the author tells The Weekly, “that every time I left the house I was sort of walking on a stage and acting a role of a woman being normal.”

Geraldine had been at her historic, shingled mill house on Martha’s Vineyard on 27th May 2019 when the call came. It was Memorial Day. Her husband, Tony Horwitz, had collapsed in the street in Washington DC, where he had been on an energetic publicity tour for his new book, Spying On The South.

Her first reaction was, “No.” No, that couldn’t be right. “Not Tony. Not him. Hilarious, bursting with vitality. He is way too busy living. He cannot possibly be dead.”

But he was. A cardiac arrest. He was 60 years old.

Who was author Geraldine Brooks’ husband Tony Horwitz?

Tony Horwitz was an adventurer as well as a serious historian. He must have seemed indestructible. He was a writer and journalist who, Geraldine writes, had covered “stories from sniper pits in Sarajevo and boats under shelling in Beirut harbour, who ducked rifle fire during the Romanian revolution and reported on two wars in the Persian Gulf, who hitchhiked across the Australian outback and followed the Pacific voyages of Captain James Cook from the Arctic circle to the edge of the Antarctic ice shelf.”

Tony had hutzpah. During the first Gulf War, he noticed that the Saudis sent their army uniforms to the dry cleaners. He bribed a dry cleaner to sell him one and, dressed as a soldier, was the only American reporter with the Kuwaiti troops as they liberated their city.

He was never, she says, operating at less than 100 per cent. It was always “all in”.

Did he have no fear? “He had a sane person’s amount of fear, but he had a possibly insane level of curiosity and ambition that drove him through the fear. And a lot of physical courage as well.”

They had met in 1982 at a party on a balcony in Manhattan. She had won a scholarship to the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and he was in the same program. She was struck by his idealism.

Working and building a life together

They would build an epic life together. Based in Cairo and then London, they would cover the Middle East, Africa, and the Balkans as foreign correspondents. Their duffel bags, she writes, were always half-packed and ready to go. “Filled with the accoutrements of foreign correspondence — short wave radios, field dressings, bricks of cash for countries that didn’t take cards, my chador, a bulletproof vest.”

While she was doing the official stories as a correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, he was out riding camels in the desert or hitching a ride “on a Goan dhow plying the mine-strewn waters of the Persian Gulf.”

They often reported together. The Wall Street Journal editors would refer to them as HoBro. “Beyond partners,” she writes, “essentially one person.”

In 1995 Tony would win a Pulitzer Prize for a series of articles on income inequality and low-wage jobs in America’s south.

“When I watched the horrific events of January 6th [the storming of the White House],” she says, “with all those really hardcore Confederate flag wavers, I was thinking Tony probably had a beer with 10 per cent of those guys.”

Geraldine is speaking by Zoom from Oxford University where she is researching her next book. She does love an archive. Behind her is a tiny arched Medieval door. “I love the name of this college,” she says smiling. “It’s called New College but it was new in the 1370s.”

Shifting away from foreign correspondence to fiction

This will be the first novel she will write without Tony’s editorial input. “I’m right at the beginning,” she says. “It’s like the first blush of a love affair where the beloved can do no wrong. I haven’t yet seen the difficulties that I will inevitably confront once I actually start writing the thing.”

When their son Nathaniel was born in 1996, she no longer wanted to go to dangerous places on newspaper assignments. (Their second son Bizu was adopted from Ethiopia in 2008 at the age of five. He was undernourished, and Tony had carried him everywhere on his shoulders for a year.)

In spite of her “zero confidence”, Tony convinced her to try to write fiction. In 2006 she won the Pulitzer Prize for her fourth novel March. The prize was, she says, “this gift-wrapped parcel you didn’t expect landing on your doorstep”. She was a visiting professor at Harvard at the time. When one of her old editors from The Wall Street Journal rang to tell her the news, “I said, ‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ and basically hung up on him.”

Tony’s non-fiction books — Baghdad Without a Map, Confederates in the Attic, and Blue Latitudes among others — were all bestsellers. “His,” said The New Yorker, “was a singular voice, full of compassion and delight and wry observations and self-deprecating humour.”

“He was infinitely curious about other people,” Geraldine says. “He wanted to understand what made people think and act the way they did.”

Continuing to collaborate

The immensity of Geraldine’s loss becomes all the more evident when you understand how creatively and intellectually intertwined they are. They would accompany each other on research trips. “A second pair of eyes and ears hoovering up detail.” Tony had a knack for “archive diving” and knowing where to look for information. They shared a taste for obscure historical detail.

“Something we were able to do for each other was to be each other’s first and last set of eyes,” she says. “We would formulate ideas together and then, before the book left the house to any outside reader, it would get a hard read from Tony. And I would do the same with his work.”

He thought she overused the words ‘desiccated’ and ‘gnarled’ and always tossed them out. She mischievously puts them back into Memorial Days. In the evenings she would see him coming down the worn path from the barn where he worked. “I’d know,” she writes “that the fun was about to begin.”

She would open the wine, “We’d pick up the conversation wherever we’d left it. Every night had a party feel: exuberant, funny.”

But, she says now, “it wasn’t all just ‘yuks’ and giggles. We also had such passionate common interests. So there was always a lot to hash out. We had a lot of opinions, as you can imagine.” More than anything she misses the evening fun. He made her laugh every single day. Now, she says, “I sometimes just feel extremely out on a limb.”

Returning to writing after such a loss

Geraldine was unable to write for the first year, and couldn’t even open the computer file which held her half-finished novel Horse. Tony had been in charge of the finances, buying and selling junk bonds, selling stocks, and playing the markets. He was by his own admission useless at getting out the toilet plunger or wrench. Geraldine did that.

Now she had to learn how to manage the money and tax bills. “All the things that he was very good at, I’m sort of ploughing my way through, learning how to manage. You do end up doing two jobs. It’s very exhausting apart from anything else.”

In February 2023, Geraldine boarded a prop plane to Flinders Island. She was going to the ends of the earth, a shack on the furthest part of the island, to do “the unfinished work of grieving”. Holding it in had “extracted an invisible price”, she writes. She had been “a fugitive from my own feelings.”

Throughout her marriage, Geraldine had compromised on one fundamental thing; Tony on many others. She had grown up in Sydney and had wanted to live in Australia. She is guided by the Southern Cross; imprinted by the Pacific Ocean. It was one of the few things they argued about. Tony had tried but America was always calling him. Its storied history fed his work, it was his passion, his muse. Now she was coming home, to a place she had been with Tony, to remember and mourn him.

Alone and taking solace from the luminous natural world, she observed the memorial days of a 35-year marriage. The wild, jagged beauty of the island, the fragrance of eucalyptus, she says, was “an incredible sustaining force for me … It’s a pretty beautiful end of the earth. It’s so gorgeous.”

What’s Geraldine Brooks’ latest novel about?

His last book had taken a lot out of Tony. In her words, it had “killed” him. A man who wrote with a singular intensity, under deadline pressure, he had got himself wired — chewing boxes of nicotine gum, taking Provigil pills, drinking gallons of coffee, throwing himself into the gym. At night, he would counter these uppers with wine. “So much wine,” she writes.

Tony knew it was unsustainable. Geraldine was researching health spas, detoxes, climbing mountains, and eating raw veggies. Everything would change after the book tour. That day never came. For at least two months, he had been sick and dying.

In Memorial Days she goes over his death in minute detail, “slowing it down, taking it in, suffering it the way I needed to suffer,” she writes.

“The recommended therapy for PTSD and complicated grief is to relive the moment and keep trying to add as much detail to it as you can instead of suppressing it,” she says. “So excavating every memory I could was part of the exercise I was undertaking.”

Geraldine began to realise that she wasn’t alone. Tony was there with her. She had his private journals and his books in which he scrawled thoughts on the margins as he read. They had a friendly posthumous disagreement over Joan Didion’s Year of Magical Thinking. On Flinders Island, she was able to concentrate on him without distraction.

“Solitude has made this space for him,” she wrote.

“I kept remembering more things. I had a lot more clarity in the complete isolation.” His journals were where he went to work things out. “That is where you take your dark nights of the soul. I thought, okay, all I know about him now is all I will ever know. But there were things in there that were surprising to me. It wasn’t the public Tony that I knew, it was Tony at his less ebullient. It didn’t bring him back in the fullness of his being.”

Geraldine opens up in her latest work

Memorial Days is a departure from a lifetime of being an objective journalist and the writing-from-a-distance of her historical fiction. It is personal. It is from the heart.

“I needed to write this book,” she tells The Weekly. “I don’t know if anybody needs to read it. It’s a book I wrote for myself. It was what I did instead of therapy.”

Geraldine’s brilliance is her ability to bring the past to vivid, sensory life. Lost worlds and forgotten people live and breathe on her pages. The reader is fully immersed in another time, another place. She draws poetically on the natural world to take us there, to give these people a voice.

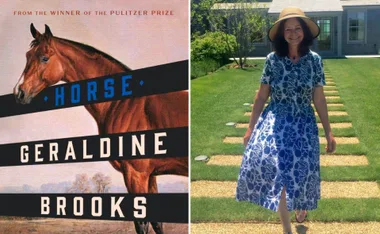

Her last novel Horse is a multi-layered book about Lexington, the greatest racehorse in US history, and the Black groom Jarret who looked after and loved him. In the American South, in the 1800s, slaves were bought and sold like horses. Her narrative moves between 1850s Kentucky and Louisiana, 1950s New York, and 2019 Washington DC. The conclusion she draws is that black people are still far from safe in America. When she was struggling with the difficult book, Tony would say, “Horse is not exactly galloping to the finish line”.

On Flinders Island, Geraldine swam and walked until, finally surfacing from the sea, she let loose the howl she had been suppressing since she got the call from Washington. She even shocked herself at its rawness echoing across an empty beach.

“That was extraordinary,” she says. “It was this subconscious eruption of a rage that I don’t think I’ve ever actually felt or expressed in my conscious life. When my eldest son read the book, he said he realised he had that as well.”

Grief and life continuing on

The grief now is for the loss of the life she had expected, and counted on. Growing old together, watching sunsets in rocking chairs. “Laughing and arguing over the news.” They had been connoisseurs of sunsets, judging them out of ten, along with a comic commentary from Tony. But growing old, slowing down — that had seemed years away. There is still so much to do.

In all the years away from Australia, Geraldine admits, there was homesickness. She wanted to come home soon after Tony’s death. Bizu would have finished high school in Sydney, but there were visa difficulties. Tony’s death has been particularly hard for Bizu who had already lost a family in Ethiopia. “The absolutely galling and infuriating thing is that he is still not an Australian citizen because they discriminate against adopted children,” she says. And then the pandemic hit.

Now, she says, “I’m in the process of trying to recentre my life but I’ve got two American children, which was very careless of me.”

Bizu is in college, and the family genes have kicked in for Nathaniel. He is the CEO of an investigative newsroom coupled with a hedge fund called Hunter Brook.

“It is not fair to say ‘see you later’,” Geraldine explains, “particularly to the younger one, who’s still in college. So I think it’s going to take me maybe a couple more years because I want him to feel like he’s got a home to come to. But I really want to recentre my life in Sydney as the boys move more confidently into their adulthood.”

To that end, she is staying in Australia for all of this summer.

What’s next for Geraldine?

Geraldine Brooks is not pretending to be normal anymore. She knows the grief will still come, but “I’ve come to terms with what my life is now,” she says.

“I have embarked on making the life I have as vivid and consequential as I can,” she writes in her memoir. Now, she makes more time for beauty. “I make it a point to notice the trees in all their various seasonal personalities. To be with the critters that share my space. A nest of baby rabbits, a coin-sized painted purple hatchling, a fluffy mallard duckling out for its first swim – these encounters more than anything else have the power to elevate me out of sadness.”

“Tell your story,” she says to those experiencing grief. “Write it down, speak to a therapist, share it with your friends. Take control of this essential moment in the narrative of your life.” As she has done.

Geraldine’s gift to us is that she has written her truth.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks, Hachette, is published on 25 January 2025.

This article originally appeared in the February 2025 issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly. Pick up the latest issue from your local newsagents or subscribe so you never miss a new issue.