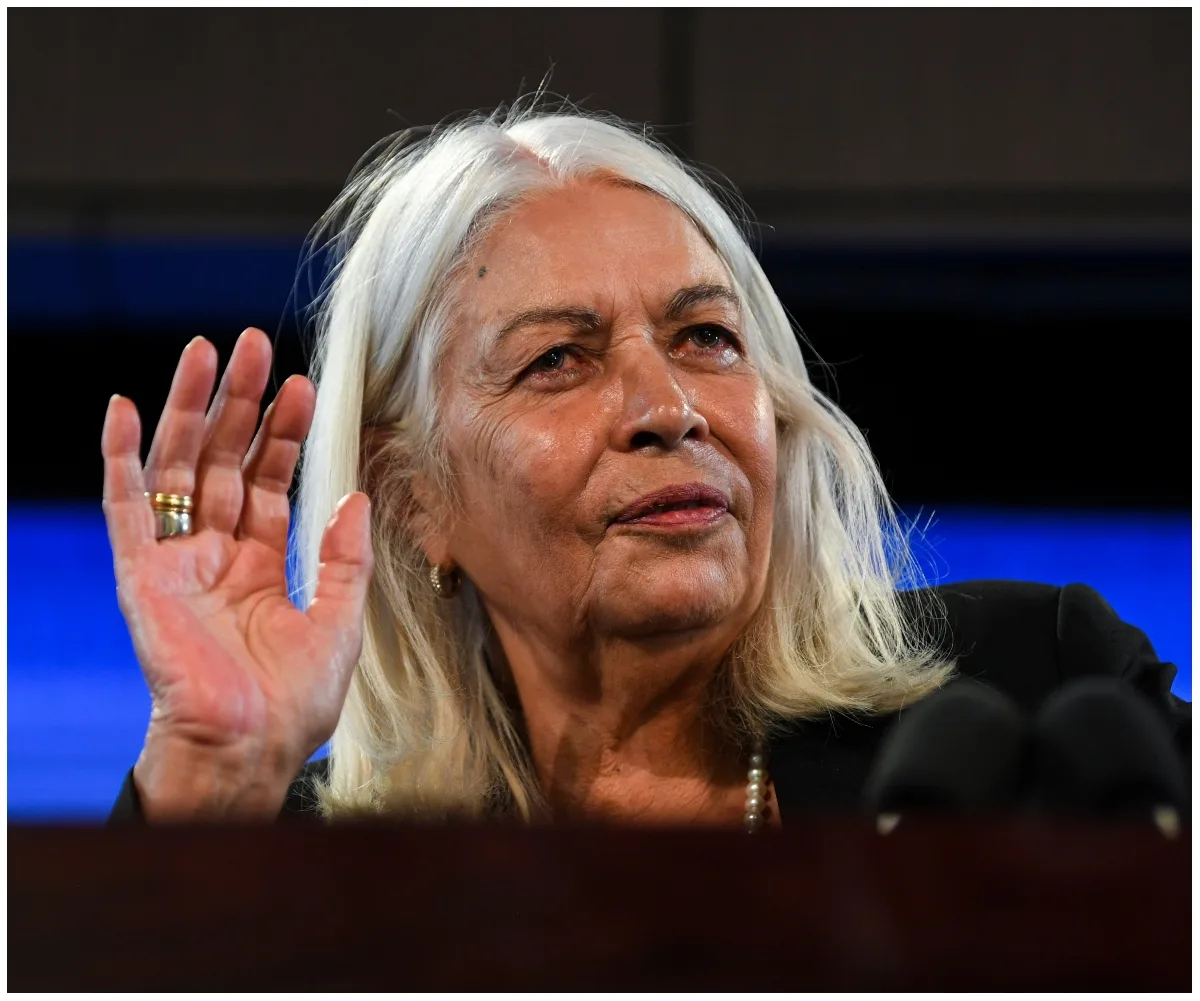

Marcia Langton is chic. Black leather jacket, knee-length skirt, musk-pink scarf, trainers and that curtain of silver-white hair that falls across eyes that have rings like Saturn, from brown through green to blue.

She cuts a striking figure, standing in the MCA cafe, Sydney Harbour sparkling behind her, drawing friends, colleagues and extended family into her orbit until tables have been pushed together and a long, animated lunch is in progress.

Love her or hate her, for 40 years, Professor Langton AO has been a formidable and controversial force in Australian public life. We’re used to seeing her on television, despatching critics with a lethal mix of academic rigour and withering scorn.

Marcia Langton is a force to be reckoned with. (Credit: (AAP))

(Credit: (AAP))I jumped in a cab this morning, expecting a quick and potentially intimidating interview with one of Australia’s most incisive thinkers. I was not expecting this glorious gathering of friends, nor Marcia’s warmth radiating at the centre of it.

“I’m glad you’re seeing me in this context,” she says when we finally find a quiet moment to chat.

“You’re seeing the real me.”

Though I suspect the real Marcia Langton is a complex package.

The great-great-granddaughter of survivors of the frontier massacres and a descendant of the Yiman people of central Queensland, Marcia inherited generations of personal grit and fortitude.

She was born in 1951 in Brisbane, and lived there until her mother, Kathleen Waddy, married a Korean War veteran, Douglas Langton.

“He was a severe alcoholic, clearly had a very bad case of PTSD and was a totally unpleasant person,” Marcia reports matter-of-factly.

“We travelled through south-west Queensland,” she recalls.

“I counted up once that I went to nine primary schools altogether. The schools were horrible, racist hellholes. The teachers were the kind of people who still advocated killing Aboriginal people,” and the kids weren’t much better.

In the little town of Dirranbandi “all the kids from school chased me home and threw rocks at me”.

Marcia found the safest place to avoid the rock throwers and her stepfather was the library.

“Nearly every town had a library,” she says. “I was usually the only reader. The librarian would let me get a book and I would sit at the table. Occasionally I was allowed to take a book home, and then I would find a really quiet place, like I would climb a tree and read up there.”

From time to time, at school, there was a lesson about “Aborigines”.

“At first, I thought, who are these Aborigines? I’ve never met any Aborigines like that?” Marcia laughs.

“It took me a while, then eventually the penny dropped. It was me!”

All the Aboriginal people she knew in regional Queensland lived in camps on the outskirts of towns, including her great aunt Teresa and her grandmother, Ruby, whom Marcia adored.

“I felt very close to them both,” she says.

“They were classified as domestic servants but they’d worked on stations all their lives, and they did really hard rural work. It was a tough life and they were victims of the most awful racism.”

“I grew up the old-fashioned, hard way,” Marcia adds.

She spent time in an orphanage, living in a tent on the edge of Brisbane and in camps. Some of those memories are difficult, but others she treasures.

“For much of my childhood, we had to cook on a wood stove; we had kerosene lamps; I had to carry water up from the river. I heard the stories from my grandmother and my great-aunt about living in the bush, and I feel close to all that. That’s what really shapes you as a person, isn’t it?”

“I grew up the old-fashioned, hard way,” Marcia tells us.

(Credit: (Getty)) (Credit: (Getty))Back in Brisbane for high school, Marcia met another great-aunt and an early influence, Celia Smith, who was an organiser for the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI).

“I saw her in town one day,” Marcia recalls, “so I went over to say hello. This was the height of the Vote Yes campaign for the 1967 Referendum, and she said to me, ‘You have to come and help us, Marcia, because you can read and write’. “It was an exciting time. The campaign was organised by ordinary people who held cake stalls and handed out pamphlets. It was a grassroots campaign and the grassroots were radical, because racism in Queensland was so severe. People on the reserves were starving.”

Another early influence was poet and activist Oodgeroo Noonuccal, then known as Kath Walker. “She was a tough lady,” Marcia says, “and she was highly literate and intellectual.” She offered a hint at the kind of future of which a young Indigenous girl from Queensland might dare to dream.

Marcia enrolled at the University of Queensland in 1969.

“I wasn’t particularly aware, at first, that it was unusual for an Aboriginal person to be there, until the master of the college I was in attacked me in vicious, racist terms in the corridor one night.”

Marcia moved into a share house with her boyfriend, the architecture student Rick Lamble, and their baby son, Ben. But again trouble came knocking.

“It was the middle of the Vietnam War,” she explains, “the FCAATSI campaign had won … I’d been going to demonstrations and organising some of the Aboriginal resistance.” This had attracted the attention of the Queensland Police, who “raided my house very early every Saturday morning. One morning, one of them threatened to kill my baby.”

“There were police who felt they could do that to Aboriginal people. There still are. We’ve all seen the record of deaths in custody and police killings. There have been several deaths even in this last year. It’s normal for us. I don’t know why people are surprised. Year after year, this is our lives.”

For Marcia, the threat to her son was the final straw.

At 18 years old, she left the university, left Brisbane and left Australia to see the world. It was a five-year odyssey that involved smuggling banned books into Papua New Guinea, running away from slave traders in New York, learning about feminism from a tall, blonde American on a train in Tokyo and about Buddhism from a laughing monk on a hair-raising bus ride in Taiwan.

She travelled with Rick as far as Hong Kong, and then she and Ben went on alone.

Marcia says: “It opened my eyes to the wider world.”

Outside Buckingham Palace, Aboriginal leaders Professor Marcia Langton, Dr Lowitja O’Donoghue, Patrick Dodson, Gatjil Djerrukura and Peter Yu.(Credit: (Getty))

(Credit: (Getty))Rain is pelting down outside the gallery. Marcia is here for the opening of Nirin, the 2020 Biennale of Sydney, which was curated by her friend, the artist Brook Andrew.

We explore the exhibits with Brook and his parents, and with Marcia’s friend, the award-winning poet and comedian Yvette Holt.

At every turn, people stop Marcia and greet her. In her pocket, her phone rings incessantly. These are the early weeks of the COVID-19 outbreak.

In four days the Ruby Princess would dock outside this very building.

Between exhibits, Marcia is planning for the temporary closure of the University of Melbourne (where she holds the Foundation Chair in Indigenous Studies and is Associate Provost) and advising on a lockdown of Indigenous communities, where the frightening health gap makes people particularly vulnerable.

One minute, she’s chatting shop with an anthropologist from Haiti, the next she is confirming a Zoom meeting with a government minister.

When Marcia returned from overseas in 1975, she settled down to earn a first-class honours degree in Anthropology, and then later a doctorate.

Her career took her to every corner of this land. She worked with the Cape York and the Central Land Councils, living for long stretches first in Alice Springs and then Far North Queensland, when her daughter, Ruby, was young.

“That was a wonderful time in my life,” she says.

Marcia has advised Prime Ministers as diverse as Paul Keating, Kevin Rudd and Scott Morrison. Julia Gillard sings her praises, telling The Weekly that “her contributions will guide our thinking about the Australia of the future”.

Marcia’s book Welcome to Country: A Travel Guide to Indigenous Australia.

Marcia has worked on some of the most significant pieces of research and legislation affecting Indigenous people over the past 30 years, from the Native Title Act to the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody and the Bringing Them Home report on the stolen generations.

Looking back, she admits that “outright wins” have been few and far between.

The Bringing Them Home report resulted in the apology but not formal compensation. Her work has helped to spotlight Aboriginal deaths in custody but hasn’t come close to ending them.

“More Indigenous women are going to prison,” she says, “and many more are dying there.”

She has been criticised by the left for hedging her bets politically and for working with ‘big mining’.

She insists that her very few forays into negotiations with mining companies have resulted in better opportunities for Indigenous people. And that “if you want an outcome, you have to work with everybody to get it”.

She once told broadcaster Phillip Adams that “there’s nothing more empowering than flying into enemy territory”.

“She has done the hard yards,” says her friend Yvette.

“She has a pulse on multiple areas of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander life. People find some of the things she says confronting. But to be where Marcia is – to have succeeded through the racism and sexism, including within Aboriginal communities – is a great testament to her. She has become one of Australia’s most formidable and engaging public intellects.”

First Australians, edited by Marcia Langton and Rachel Perkins.

Marcia had been called upon to co-chair the Voice Co-Design Senior Advisory Group with Professor Tom Calma.

She explains: “The Turnbull government appointed a Referendum Council, which held dialogue meetings around the country, led by Pat Anderson and Megan Davis. The result was the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which called for a voice to parliament, a makarrata [or treaty commission] and truth-telling.

“The Voice was to be a body to represent all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and advise the parliament on legislation that affected them, but the details were not included in the statement, and this remains a problem. A Voice referendum was briefly favoured by [Indigenous Australians] Minister Ken Wyatt, but the Morrison government back-pedalled furiously on that.”

The group she chaired with Tom Calma worked alongside national and regional bodies towards a blueprint for a Voice to Government and reported to the minister.

In 2023, Australia voted against enshrining the Voice in the Constitution, but Marcia’s emphatic stance still holds.

“If it is not enshrined in the Constitution, another government will come along and say, ‘I don’t like the look of those Aborigines, let’s get rid of that’. What we need in the Constitution is a simple, elegant clause that recognises the First Peoples and guarantees that there will be a mechanism for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to have a say in the legislation that affects their lives.

“Aboriginal people should have a say in what happens to us … We would be here for the next four hours if I was to go through every advisory group and commission that has been invented and abolished by Australian governments in Indigenous Affairs.

“It’s one of the reasons for the terrible closing the gap outcomes … We have to draw a line in the sand, stop playing games, find a model that will work and stick to it.”

We’re sitting in an old-school cafe opposite the MCA. It could almost be a mirage, conjured by Marcia’s memories of Brisbane in 1965.

We shared an umbrella crossing the street but we both had sodden scarves and soggy feet, so we ordered hot, strong tea and carrot cake with two scoops of vanilla ice cream.

We’re discussing the hate mail and the death threats. Her staff used to destroy the worst of them before she saw them, but now she keeps them all in a box in her office.

“A lot of young people ask how I keep going,” she begins.

“I’m a very lazy Buddhist, but Buddhism has helped. You can be deterred from your pathway in life by the constant hatred or you can put up a shield and fulfil your destiny. I think I’ve been fairly successful at that, and I think Buddhism has given me strength and discipline. It’s helped me to live every moment as if the next moment will be my last. So somebody kills me right now, I’m having a good time here, eating gorgeous cake.”

It is damn fine cake, but are there times when Buddhism isn’t enough, when the shock jocks get too much? Does she hurl things around the house when nobody’s looking?

“Yes, yes. I’ve broken a few phones, and destroyed a few television sets,” she chuckles.

And have there been times when she’s worried for her family?

0“I did my best to protect my children from the worst of it,” she says. “Sometimes I failed.”

She tried also to protect them from racism and the full, ugly violence of their family’s, and Australia’s, history.

“My daughter was very angry with me, that I hadn’t told her all the horror stories,” she says. Though when Ruby was just nine years old, Marcia took her back to Yiman country to see what remained of the mass graves of her ancestors.

“My son saw more of it because we lived in Alice Springs when he was young. He saw the discrimination every day, and it made him angry. Both of them have a keen sense of right and wrong and historical justice. I’m very proud of them.”

Ben, now 50, lives in New Zealand with his partner and Marcia’s three grandchildren.

“I don’t see my grandchildren enough,” she says, “but we have good times when we’re together.” Ruby is 31 and works in law in NSW.

Marcia lives in inner-city Melbourne but she believes that “home is where the heart is. Being with my children, speaking on the phone to my grandchildren, having my dog, Finnegan, with me, having my friends around me: it doesn’t matter where you are, love is really home, isn’t it?”

Even so, says Yvette, “it’s a sight to behold, watching Marcia come home. She walks in the door and lets go of the day. She’s a fantastic cook. She can cook any dish, any nationality. It’s a very quiet, peaceful side of her. She loves her garden.

1“She loves walking her dog, sometimes in the middle of the night. Some of the best times we’ve had have been midnight walks with Finnegan. Or feeding the birds. First thing in the morning, before she hits the emails, the mobile phone, the shower, she scatters birdseed and feeds flocks of lorikeets that fly into her backyard. If I’m house-sitting, there’ll be a text message every day: have you fed the birds? She buys kilos of seed.”

Weeks pass, Australia goes into isolation, then one day Yvette calls from Alice Springs.

“I’ll just tell you one more thing,” she says.

It was the second week of lockdown. Marcia told me that she had to buy a microwave and asked if I would come along and help. I suggested we go to Kmart but no, she bought a very good – and fairly expensive – one … And we delivered it to a woman she didn’t know well who lived in social housing in Fitzroy. Marcia had seen her callout that morning on social media. That’s not an unusual thing. The rest of the country may not see it, but that generosity is there in her spirit.

I ask whether we risk creating a portrait here of Saint Marcia. She laughs. “I’ve seen the good and the bad,” she says. “She’s no saint, but she’s a caring, generous friend.”

Marcia with Ruby.

(Credit: (Instagram)) (Credit: (Instagram))It’s the third day of Nirin and Marcia is packing up tonight and driving home to Melbourne at first light. She’d hoped to stay longer, spend more time with her daughter who lives not far out of Sydney, but there’s just too much to do.

Marcia is now 72 and has no intention of slowing down.

2Her grandmother lived to her nineties, and Marcia has a good 20 years’ worth of projects still on her to-do list.

“I have a few books left in me,” she says restlessly. “I have about six sitting in my head. It’s like living with ghosts.”

She has already written dozens of academic and popular books, from a treatise on Indigenous filmmaking through a Boyer lecture to, more recently, Welcome to Country, a Travel Guide to Indigenous Australia, and Welcome to Country, an Introduction to our First Peoples for Young Australians.

She is burning to write more about Indigenous knowledge of the natural world.

“People don’t understand how much the colonisers destroyed,” she says, “but equally, they don’t understand how much survived. There are living Aboriginal knowledge systems and they’re very precious.

“I think that’s the story of Aboriginal Australia: enormous resilience and an obsession to preserve our cultures. It’s about preserving more than the environment – it’s about a worldview, a set of values, who we are as people, our souls. It’s about our souls.”

She believes Australia is at a tipping point – that a representative body and eventually constitutional recognition of First Nations people might be just a heartbeat away, and could change this country for the better.

“Why would you not want to have a modern Australia founded on 65,000 years of [Aboriginal] histories and societies, then the addition of the British institutions and also multiculturalism? Australia will come of age when all those things are recognised, and it will happen,” she says finally.

3“You can’t ignore the obvious forever.”