Content warning: The following story discusses violence against women.

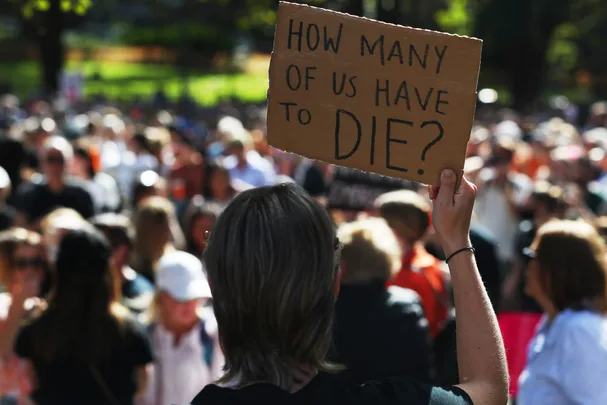

As battle-weary women across the country dusted off their “Enough is Enough” signs and took to the streets again, anger churned their weary frustration into resolute determination. Too many women had died. Something needed to be done.

That same weekend, emergency service workers responding to a house fire in a southern suburb of Perth had found the body of a 30-year-old woman in a bedroom. Her name was Erica Hay. She was the mother of four children. Her partner, Luke Hanif Sekkouah, 35, was later charged with murdering Erica and setting their home on fire.

At the time of writing, Erica’s senseless death, allegedly at the hands of someone she knew, brought the number of women violently killed in Australia this year to 27. If the current rate continues, four more Australian women will die by the time you read these words.

Those people marching are right. Something needs to be done. But the same was said in 2013 as 30,000 Melburnians filled Sydney Road in memory of Jill Meagher, Sarah Cafferkey and Tracey Connelly. And again in 2018, when the murder of Eurydice Dixon drew 10,000 mourners to Princes Park and prompted nation-wide Reclaim the Night marches.

The march in Cairns was particularly potent coming just days after the body of Toyah Cordingley 24, was found on Wangetti Beach, south of Port Douglas. As women and allies gathered again this year, their anger reached a nadir. Our country is experiencing an annus horribilis and it is only May. Last month started with a rally in Ballarat condemning violence in the wake of three lives lost: Samantha Murphy, 51, Rebecca Young, 42, and 23-year-old Hannah McGuire, who was found in a burnt-out car.

The next day, five more women died at a shopping centre in Bondi. Among them was new mother Ashlee Good, 38, who was stabbed as she put herself between her infant and the assailant. Bride-to-be Dawn Singleton, 25, Jade Young, 47, Pikria Darchia, 55, and economics student Yixuan Cheng, 27, were also murdered. Faraz Tahir, 30, a security guard, lost his life too. The offender was battling a complex set of problems. Nevertheless, NSW Police Commissioner Karen Webb said it was “obvious” he targeted women.’

The news was still fresh when another death was reported. A 28-year-old mother from Forbes, Molly Ticehurst, had been killed. Police charged her ex-partner Daniel Billings, who had been released on bail despite facing four charges of stalking and three charges of rape. Molly spent the last days of her life terrified he would come for her.

The grim but necessary womendriven tallying of fatalities, Counting Dead Women Australia, tells us that in recent years Australian women have been killed at a rate of roughly one a week. This year, the rate is nearly one woman every four days.

The Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence Commissioner, Micaela Cronin, has declared it a national crisis. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese agreed. Something needs to be done. But how to end the slaughter?

“The focus for decades has been on women and how to protect women and how to keep women safe,” says Patty Kinnersly, CEO of violence against women prevention organisation Our Watch.

“There’s almost been a silence about the people who are perpetrating the violence.” But that is changing, she says, and she is heartened by discussions about the relationship between certain interpretations of “how to be a man and violence against women”. Ten years ago, she adds, you couldn’t have had this conversation. Amid the recent demonstrations, that conversation was front and centre.

Senator David Pocock said, “This is, first and foremost, a men’s issue.” The Federal Attorney-General, Mark Dreyfus, asserted it cannot be left to women to do something about this. The change in focus is needed for all our sakes.

Rigid views of masculinity are harmful to both women and men. The solution needs to be cultural. We all need to own this, as was highlighted by former tennis star Jelena Dokic, who wrote on Instagram that, “Nobody called out [her father’s] disturbing, aggressive and concerning behaviour. Everybody just laughed. While behind the scenes I was being beaten, kicked and punched and told I would be killed.”

The solution can also be political, as we saw when NSW Premier Chris Minns announced he had sought urgent advice on whether law reform was needed of bail laws, particularly as they related to domestic violence, in the wake of Molly Ticehurst’s death.

It’s pastoral too. Of the men charged over the Ballarat murders, Patty said, “Those young men, over the last decade, would have come into contact with at least two levels of schooling, with several sporting organisations, maybe with church, certainly in an online environment and certainly with friends and peers and aunties and uncles and things.

When they expressed disrespectful attitudes towards women, were they challenged?” It’s logistical. Victoria’s 2015 Royal Commission into Family Violence made 227 recommendations that included everything from updating and centralising information technology so law enforcement agencies could share information, to police officer training and changing the physical structure of court buildings to make them safer for victims.

It’s financial. Domestic Violence NSW has asked the state government to correct years of underfunding of domestic violence services, and to address the housing crisis. The Bondi attack also reignited calls for more money for mental health services.

The cascade of tragedies has forced crisis meetings. We are two years into the 10-year, $2.3 billion National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children, but Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has acknowledged the need for “immediate measures and responses”. Women and allies may have despaired, as they trudged like Sisyphus, begging for change, but their outrage has power.

It was only 10 years ago that Rosie Batty showed us how much good one voice can do. This year, thousands have raised their voices. It is a long and difficult road to change. But we will march on until there’s no more need to say something needs to be done.

If you or someone you know has been affected by any of the issues raised in this article, help is always available. Call 1800 RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit their website.